With Fire in His Eyes: The Burning Mission of Rav Aharon Kotler

| December 20, 2022Rav Aharon Kotler inspired a Torah revolution on three continents — but that’s just part of the story

Photos: BMG Archives, Agudah Archives, DMS Yeshiva Archives, Wolfson Family, Hoberman Family, Kamenetsky Family, National Library of Israel, US Dept of State, Prof. Chaim I. Waxman, YIVO, Torah Umesorah Archives, Chinuch Atzmai Archives, Perr Family, Golding Family, Bunim Family, TAJ Art and Judaica, Feivel Schneider

Boro Park, Brooklyn, late 1950s

A child is playing outside a shul. He is approached by a Mirrer talmid who spent the war years in Shanghai. The man asks him incredulously, “How can you play outside when Rav Aharon Kotler is delivering a shiur? How can you lose your chance to hear him speak?”

The boy obligingly goes inside and listens, not understanding a single word.

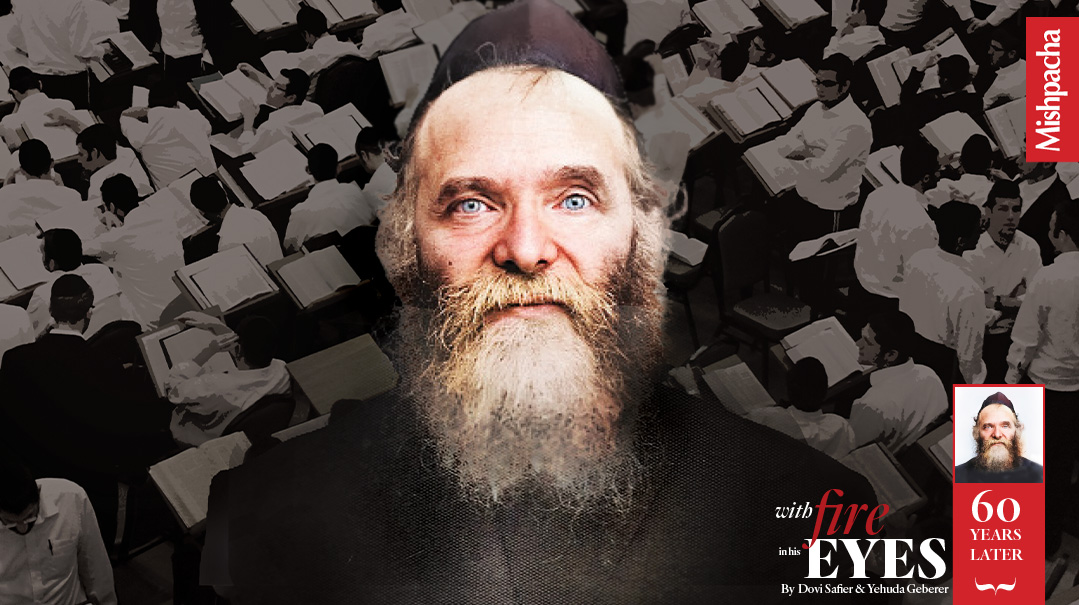

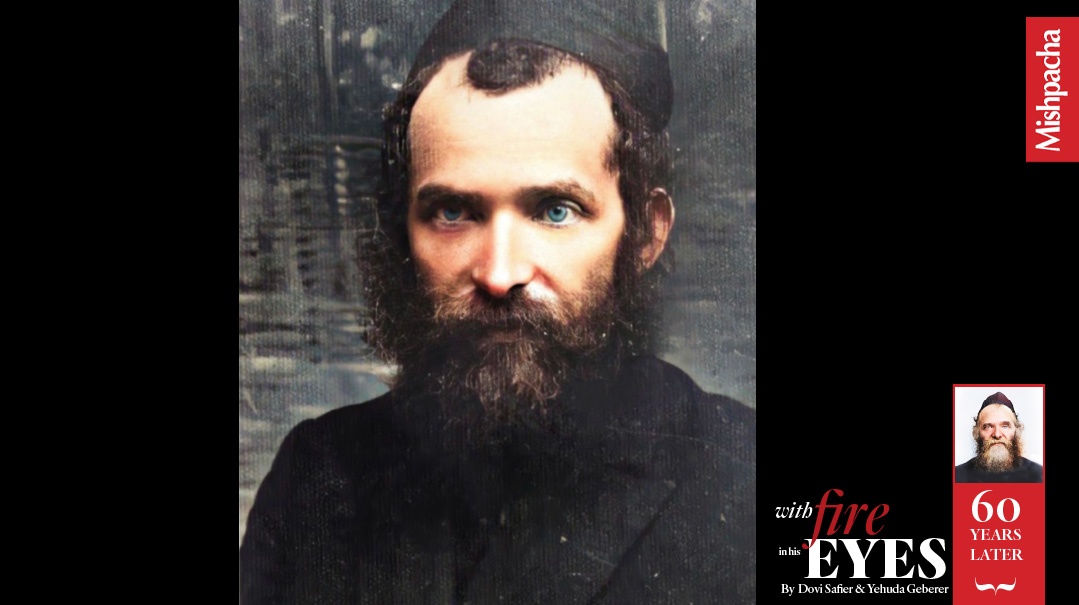

Decades later, he still recalled the scene: “I saw an older man speaking with a passion I had never seen before or since. His face was beet-red with excitement and exertion. His flaming blue eyes bore into the souls of all present. The energy he exuded, the pathos of his speech, and the glow of his face made it a surreal experience. Despite not having understood, that image is engraved in my mind for eternity.”

Such was an encounter with Rav Aharon Kotler.

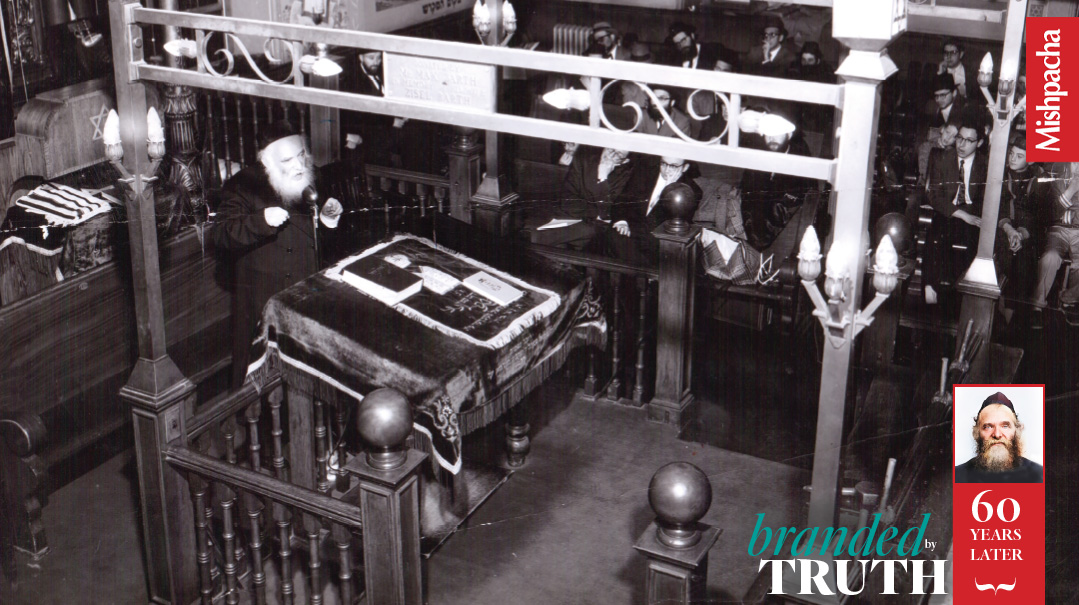

Rav Aharon delivering a shiur at the Bialystoker Synagogue on New York’s Lower East Side

Rav Aharon was the Rabban Yochanan Ben Zakkai of his time, tasked with picking up the pieces after the staggering destruction of the Holocaust. With penetrating vision and powerful determination, he inspired a Torah revolution on three continents — but that’s just part of the story.

For more than 20 years prior to his arrival in America, Rav Aharon Kotler was one of the leaders of Torah Jewry in Europe, standing alongside fellow gedolim a generation older than he. Even then, he displayed a sense of concern and responsibility for the wider Torah world, taking initiative and accepting burdens far beyond his own yeshivah. That wide-lens view accompanied him throughout his life, marking him not only as the Rosh Yeshivah who transformed America’s relationship with Torah learning, but as the leader who burned with a constant urgency to rescue, restore, initiate, rally, and support the growth of Torah wherever Jews could be found.

IT was the spring of 1941, and a small crowd gathered at a little shul on Clinton Street on the Lower East Side of New York. Rav Aharon Kotler, rosh yeshivah of the famous Kletzk yeshivah, had recently arrived in the United States, and they’d come to hear him speak — as much out of pity and respect as out of ideology.

The attendees were an assemblage of senior yeshivah students from NewYork yeshivos such as Torah Vodaath, Rabbeinu Yaakov Yosef (RJJ), and acouple of others. The rosh yeshivah was alone, separated from his students —albeit not for lack of trying to bring them to safety. He had recently met withAgudath Harabonim emissary Dr. Samuel Schmidt in Yanova, Lithuania, wherehis yeshivah had relocated. Rav Aharon pleaded with Schmidt to help arrangea transfer of the fragmented Lithuanian yeshivah world to the United States.

But it was not to be. Just weeks after Rav Aharon’s arrival in Americaon Erev Pesach of 1941, the Nazis invaded Soviet-occupied Lithuania andbrought an end to the golden age of Torah study in Eastern Europe. Most ofthe Kletzk students, the rest of the yeshivos, the masses of Lithuanian Jews, and communities across Eastern Europe would bemartyred in the Nazi carnage of the coming years.

On that day in 1941, Rav Aharon described thechain of Torah that commenced at Har Sinai andwas composed of links of various quality — someof precious metals and others of baser materials.He described the historical sequence of thetransmission of Torah from Rabban Yochanan benZakkai through the Rishonim and finished withrecent Torah leaders: Rav Chaim Brisker, Rav MeirSimchah of Dvinsk, and Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzinski.Reaching a fevered pitch, he began his plea, urgingthe assembled yeshivah students to forge anotherlink in the dynastic chain.

This was their introduction to Rav Aharon Kotler, and to his unbending assertion that there is only one way to produce Torah leaders of caliber: through channeling all the powers of one’s will and intellectual capacities toward the study of Torah. Without total submission to Torah learning, he said, without fundamental lomdus, toil and perseverance, Torah cannot takeroot in the individual’s soul, cannot change hisbeing or essence. There was no time or place fordistractions.

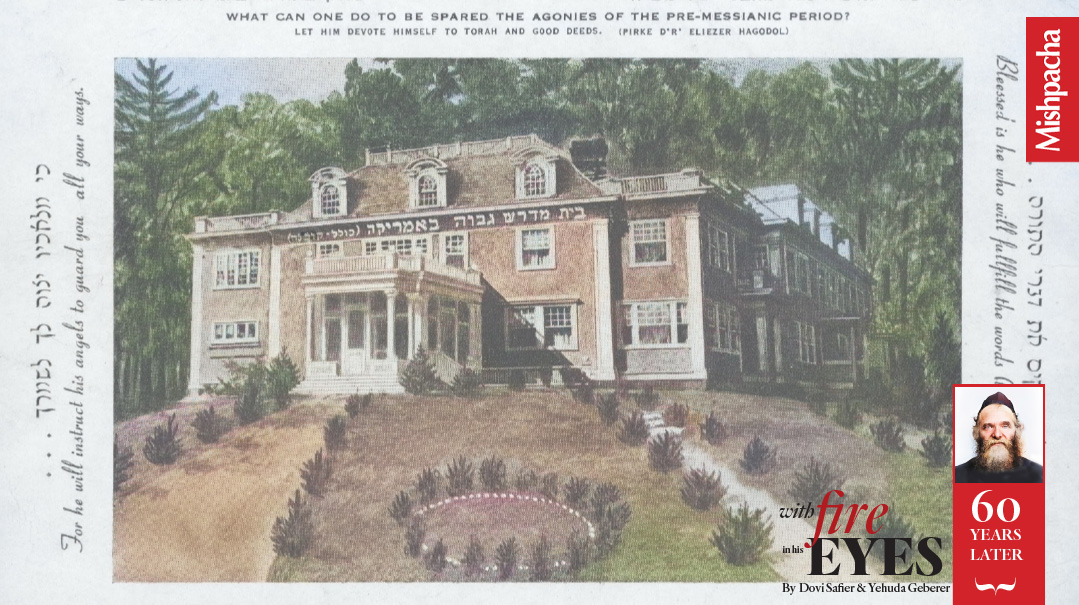

That historic talk articulated Rav Aharon’s ideology, mission, and contagious energy. It laid the groundwork for the establishment of Beth Medrash Govoha in Lakewood, and for a seismic change in America’s attitude toward Torah learning and living. Rav Aharon was never satisfied with words alone; this was a call for action. And act he did, with a fiery resolve that ignited a growing cadre of talmidim, activists, and supporters to act as well.

“Did you ever see the Rosh Yeshivah’s photograph? Do not accept it; for neither artist nor camera can capture the fire in his eyes, the radiance on his face, the exhilaration of his presence. The image engraved in one’s memory is more accurate than any photographic or artistic rendition. -Rav Shaul Kagan

Chapter One: Sunrise in Sislovitz

Son of Sislovitz

February 2, 1892 / the fourth of Shevat 5652. A day that lives in infamy in the annals of the yeshivah world.

Russian authorities shuttered the doors of the Volozhin Yeshiva, ending the nearly 90-year reign of the “mother of all yeshivos.” The prophetic words of Shlomo Hamelech promise that, “The sun rises and the sun sets.” The Gemara notes that in his formulation, the sun rises before it sets; a metaphor for the nhistory of Torah transmission. The Torah will begin to rise in a new place before its current locus goes dark.

The news of Volozhin’s closure spread quickly as students returned home to their respective cities and villages, among them the town of Śvisłač (Sislovitz), located 250 kilometers from Volozhin in Grodno Province, where a respected alumnus of the yeshivah, a rav named Rav Shneur Zalman Pines, was hosting a bris for his son, whom he named Aharon. “Zeh hakatan gadol yihyeh,” the mohelannounced. Little did anyone realize that the sun was beginning to rise onceagain, and few would play a larger role in lighting upthe dark sky than youngAharon.

Arke (as he was known) was born into a family that traced its lineage back to the Megaleh Amukos and Rashi. The name Pines was derived from the words, “al pines — by a miracle,” marking a miraculous salvation that took place generations prior.

Rav Shneur Zalman, the third son of Rav Moshe Pines, was born during the reign of Czar Nicholas I, when the dreaded Cantonist laws were in effect. In order to evade conscription, Rav Moshe obtained papers that named Shneur Zalman the only son of the Kotler family, thus exempting him from the draconian Czarist decree. While he reverted back to the prestigious Pines name later on in life, his son Arke would maintain the Kotler surname, and ensure that it would become a name enshrined with gold letters in the history of the Jewish nation.

Rav Shneur Zalman was described as “short, thin, and weak,” traits that young Arke inherited. But thankfully, he likewise inherited his father’s sharp mind and endless capacity to absorb knowledge, though it was his legendary diligence — an unusual intensity and zeal — that caused him to stand out among his peers.

Arke became the child prodigy of Śvisłač. One of his childhood friends later reminisced in the town’s Yizkor (memorial) book: “I would visit the house of the rabbi as a friend of the delightful child Arke (today Rav Aharon Kotler). We studied together with his father of blessed memory, and we spent many a mishmar (all-night learning session) together. The house of the rabbi shone with the splendor of(his son) the gaon. Arke was extolled for his sharp answers to the teachers’ questions.”

Another Śvisłač resident recalled that “the whole town marveled at how the Rav’s little boy could recite all of Tanach by heart.”

FRIENDS FOR LIFE: From their joint youth in Slabodka, through their common experience as talmidim of Slabodka, their traversing the Atlantic and eventually assuming positions in the rebuilding of the postwar Torah world, Rav Reuven Grozovsky with Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky & Rav Aharon shared destiny and leadership

Socialist Winds

Arke may have had a shining reputation, but his childhood was marred by tragedy and pain. He watched as those around him strayed from the faith their families had maintained for generations.

Most of the 2,000 Jewish residents in Śvisłač worked at local tanneries, which dominated the local economy. As the Jewish Socialist party, the Bund, began to make inroads in the region, workers began to organize and demand better salaries and working conditions. The Bund sought to organize the Jewish working class, and to remake Jewish identity as well, with Yiddish culture replacing religious observance. Oftentimes it wasn’t limited to mere abandonment of religion; it was openly hostile toward mitzvah observance.

Unfortunately, the trend toward socialism wasn’t limited to labor unions, and ambivalence toward religion soon turned into animosity. In his memoirs, Śvisłač resident David Lewis (later a leader in the Canadian Bund) described how soon after the onset of Shabbos, local youths would paste their leaflets to the door of the main shul in town, knowing that they couldn’t be removed by the Shabbos-observant attendees.

Cheder attendance began to dwindle, and in 1900a modern Hebrew school was opened. By 1915, a secular Yiddish school was dedicated in town, and within four years the cheder was shuttered.

Like most devout Jews in Śvisłač, Rav Shneur Zalman struggled to protect his children from the winds of change sweeping Eastern European Jewish youth. In 1896 his wife Sarah Pesha passed away and he was left to raise his children alone. His elder daughter Malka was ensnared by the secularist movements that captured the hearts and minds of the local youth. (While its unclear what became of his son Moshe, thankfully, his younger daughter Devorah was spared from this plague.)

A controversy erupted over the return of a former rabbi to town. Rav Shneur Zalman refused to take part in the polemics some were hurling at his opponent, but those close to him saw that he was suffering greatly. In 1903 he died suddenly, a death that many blamed on his pain over the upheaval. Young Aharon was left alone, bereft of both parents in a volatile world.

Two months later, following a short stay in Minsk, the 11-year-old orphan was sent by his uncle Rav Yitzchak Pines to study in the yeshivah in Krinik, under the leadership of Rav Zalman Sender Kahana- Shapiro, whom the Pines family was acquainted with from Volozhin.

In Krinik, Rav Aharon joined a seasoned group of older students, but had no difficulty keeping up and even standing out with his quick mind and impressive diligence. After studying for two zemanim in Krinik, Arke was ready to move on, and is said to have traveled to Slabodka where he joined Yeshivas Knesses Beis Yitzchak. The yeshivah was in the process of welcoming a new rosh yeshivah, Rav Baruch Ber Leibowitz, whose shiurim would dominate the Lithuanian Torah landscape for the next 35 years.

Back in 1897, a portion of the Slabodka student body revolted against the Alter of Slabodka’s educational approach. This soon escalated into an organized resistance to the mussar movement known as the “Pulmus Hamussar.” Ultimately, the Alter departed from his yeshivah and established Yeshivas Knesses Yisrael. He was followed there by the rosh yeshivah Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein and a few dozen loyal students. The majority of students, however, chose to remain with the Rav of Slabodka, Rav Moshe Danishevsky, until Rav Chaim Rabinowitz (known to posterity as Rav Chaim Telzer) was hired as rosh yeshivah.

In 1904 Rav Chaim Rabinowitz departed for Telz and was replaced by the rav of Halusk and a prime student of Rav Chaim Brisker, Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz. Little is known about the time Rav Aharon spent at Knesses Beis Yitzchak, but the presence of the young student caused a stir in Slabodka, so much so that a plan was eventually put into motion to try and bring him to the Alter’s yeshivah, Knesses Yisrael.

Roots and Branches

Rav Zalman Sender Kahana-Shapiro

As a newly bereft orphan, young Aharon Kotler was sent to study in the yeshivah in Krinik, under the tutelage of Rav Zalman Sender Kahana- Shapiro.

One of the Torah giants of his time, Rav Zalman Sender was a great-grandson of Rav Chaim Volozhiner through his daughter Relkeh’s second marriage. In Volozhin he was a student of his cousin the Beis HaLevi, and was so attached to him that when the Beis HaLevi left Volozhin to assume the rabbinate of Slutzk in 1865, he joined him. In Slutzk he was paired with the Beis HaLevi’s son Chaim, who would soon light up the world as a young rosh yeshivah in Volozhin.

The story is told that the Beis HaLevi asked the two youngsters which was a bigger lamdan. “I can’t answer,” Rav Zalman Sender replied. “If I say I’m bigger, I’ll be a baal gaavah and if I say Rav Chaim is bigger, I’ll be a liar.”

Rav Chaim then riposted with glee, “I say that Zalman Sender is both!”

In addition to his spiritual prowess and unusually sharp mind, Rav Zalman Sender was musically talented and composed several niggunim that became mainstays in Lithuanian yeshivos. His nusach for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur became popular as well. Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz — also known for his musical gifts — shared how on Seder night, the townspeople of Krinik would gather outside Rav Zalman Sender’s window to hear him sing.

In 1885 he was appointed rabbi of Maltch. When Yeshivah Knesses Beis Yitzchak opened in Slabodka in 1898, Rav Zalman Sender was among those invited to become its rosh yeshivah (and according to one source, even spent a few days there). Community leaders in Maltch feared losing their rav, and offered to establish a yeshivah for him in town. Rav Zalman Sender accepted and shortly thereafter opened a yeshivah there. He named it Anaf (branch of) Etz Chaim after his alma mater of Volozhin. In doing so, he expressed his hope to pay tribute to his illustrious forebear, and to imply that his yeshivah was to be a resurrection of the “mother of all yeshivos” which had been shuttered several years prior.

Among his students were his brilliant son Rav Avrohom Dov Ber Kahana- Shapiro (the Dvar Avraham), Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky, Rav Yecheskel Sarna, Rav Avrohom Yaffen, Rav Isser Yehudah Unterman, and Rav Yehuda Levenberg (later rosh yeshivah of New Haven).

In 1903 he was offered the rabbinate of the larger town of Krinik, which he accepted on condition that he could open a yeshivah there as well. Rav Shimon Shkop replaced him in Maltch in both capacities.

During the first World War he fled eastward, eventually making his way toward the land of Israel where he settled in Yerushalayim until his passing in 1923.

Rav Aharon and Rav Boruch Ber: They were once walking together and came to a door. Rav Aharon refused to enter until Rav Boruch Ber went first. Rav Boruch Ber wouldn’t hear of it. He locked his arm with Rav Aharon’s arm and they walked through the door together

The Boy in the Butcher’s Shul

Prior to Pesach of 1905, Rav Aharon journeyed to Minsk and joined a kibbutz of older talmidim at the Katzovisheh (Butchers’) Shul. Many of the more than 100 shuls in Minsk belonged to the various workers’ guilds common to urban life at the turn of the century. There were shuls for carpenters, shoemakers, tailors, milliners, water carriers, kehillah officials, and even rag-makers.

Some of these shuls hosted “kibbutzim,” small groups of young men that studied there. Local families belonging to the shul wouldtake responsibility for feeding the students and provided them with a modest monthly stipend. A handful of these improvised yeshivos became formal institutions and gained some renown, such as the famous “Blumka’s Kloiz” and a yeshivah run by Rav Shlomo Goloventzitz, which served as a feeder for Slabodka.

Rav Shmuel Charkover, rosh yeshivah of Bais Hatalmud, shared with his student Rav Michel Shurkin that as a 14-year-old, Rav Aharon penned a kuntres on Maseches Mikvaos that “dazzled the Torah world.” Minsk began to take notice of the young boy learning diligently in the Butchers’ Shul. In recognition of his status, as well as the fact that he was an orphan, Rav Aharon was provided by the Katzovisheh Shul with a significantly larger stipend than others.

In Minsk, Arke became acquainted with another budding Torah scholar just a few months his

senior named Yaakov Kamenetsky, with whom he developed a close relationship. Rav Yaakov, who wasn’t prone to hyperbole, later recalled his mother’s reaction upon meeting his friend: “Who is this boy? The Shechinah shines from him!”

Minsk’s spirit of Toras chesed was a tradition from the city’s great rabbinic leaders of the 18th century: Rav Leib Baal Hatosafos, his grandson Rav Aryeh Leib Gunzburg, the Shaagas Aryeh; and Rav Yechiel Halpern, the Seder Hadoros. Local rabbanim occasionally delivered shiurim to the students, but otherwise these improvised yeshivos generally lacked formal structure and authority. This arrangement presented an open door for the various ideological movements sweeping the increasingly radicalized Jewish street.

These tempting ideologies threatened to ensnare many of the day’s finest young Torah minds. A savior arrived in the form of Rav Reuven Grozovsky, an older student of the Alter of Slabodka. He sought out Arke out of concern for the potential adverse influence of the modern movements sweeping through Minsk.

Rav Reuven decided to ensure that Arke would be protected by bringing him to Slabodka where the great educator, the Alter of Slabodka, Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel, could take him under his wing.

Even the trip from Minsk to Slabodka required planning; namely, a donor who would fund it. To appreciate this saga, we fast-forward a half-century to Tel Aviv, Israel:

In the mid-50s, Rav Mordechai Shapiro, a talmid of Rav Aharon Kotler ztz”l, traveled to Israel. One Erev Shabbos he saw a small kiosk in Tel Aviv, and someone asked the proprietor for a pack of cigarettes. The man looked up and asked, “Mah hashaah — what time is it?”

“Shteim-esrei v’chetzi — twelve-thirty,” came the answer.

“Well, I don’t sell cigarettes after chatzos on Erev Shabbos,” the man said.

That piqued Rav Mordechai Shapiro’s interest. His curiosity got the better of him, and he struck up a conversation.

“Shalom aleichem, what’s your name?”

“Yankele Ochsenkrug,” the proprietor said.

“Where are you from?” Rav Mordechai went on.

“Minsk. And where are you from?”

“America,” Rav Mordechai Shapiro answered.

“America. A Yid fun Amerike,” the man mumbled to himself. Years ago he knew a little child in Minsk, and he remembered giving money for this child’s ticket to Slabodka. Years later he heard that this child had somehow ended up in America and opened a yeshivah.

“Well, vos is zein nomen — what’s his name?” Rav Mordechai asked.

“Arke Sislovitzer,” replied the old man.

He explained that he used to be a butcher in Minsk, and he took a kopek from every ruble he made and put it aside to support Torah learning. There were a few precocious children in the shul there, and he paid for train tickets for two of them to go to Slabodka. He couldn’t remember the name of the other child, but this one he remembered, Arke Sislovitzer — he was a brilliant little child.

“Arke Sislovitzer is Rav Aharon Kotler,” Rav Mordechai told him. “He’s building Torah in

America!”

When Rav Mordechai returned home, he had the opportunity to speak at a Torah Umesorah convention, and was still taken by this story. He related the story about a poshute Yid who set aside a kopek from his earnings for hachzakas Torah. When he reached the punchline — Arke Sislovitzer, Rav Aharon Kotler! — there was suddenly a commotion at the head table. Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky stood up, walked over to Rav Mordechai and said, “I was the second child.”

Rav Aharon as a student in Slabodka, seated second from left

Space in Slabodka

Following Pesach of 1906, Rav Aharon arrived in Slabodka together with RavYaakov. The following day the two were called in to the rosh yeshivah, Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein, for their entrance exam.

Rav Moshe Mordechai presented a section of the Ketzos Hachoshen and asked them to return with a challenge to the author’s discourse — which they succeeded in doing. They were then instructed to wait for the Alter to return from Kelm where he had spent Yom Tov with his family.

The following day saw the Alter’s return. He examined the two boys with his piercing eyes. After a short while, he informed them that the yeshivah was likely too crowded for the upcoming zeman. “Wait until all of the bochurim return,” he told them, “and perhaps there will be some space for you.”

Dejected, they exited the room. Fourteen-year-old Rav Aharon, however, noticed something amiss. After all, hadn’t they been “recruited” by a trusted student of the Alter? The Alter, in his genius, was likely testing their resolve. Without hesitating, Rav Aharon announced, “Why don’t we go study at the other yeshivah in town, (Knesses Beis Yitzchak)?”

The older student who was accompanying them quickly slipped away and reported what he’d heard to the Alter, who beamed with pride. They’d passed the test with flying colors. A few minutes later, they were offically welcomed into the yeshivah.

It didn’t take long for Arke Sislovitzer to be noticed. He was only 14 years old, but that didn’t stop him from being outspoken in shiur, challenging the rosh yeshivah, Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein. He was so short that he stood on a chair in order to be heard. The Alter cared for the neophyte as he would his own child, hosting him at his apartment adjacent to the yeshivah for Shabbos and Yom Yov meals alongside some of his closest older students.

In Slabodka there was something of a caste system, with older students rarely acknowledging their junior counterparts, let alone conversing with them. Most younger students were placed in the Ohr Hachaim Yeshivah Ketanah affiliated with Slabodka, known as Rav Hirschaleh’s yeshivah for its founder Rav Tzvi Hirsch Levitan. Rav Aharon’s immediate placement in the yeshivah proper awarded him unique status.

His stanzia (lodging place) was two blocks from the yeshivah, and the young teenager was often fearful to walk alone late at night. On occasion the Alter would accompany little Arke to his place of lodging. These efforts of the Alter to protect the young prodigy would pay dividends for generations to come — he would later say that it was worth maintaining the entire yeshivah with all of its hundreds of students if only to produce that one student, Arke Sislovitzer, who eventually became the great Rav Aharon Kotler.

The Vishker Illui, Rav Yaakov Safsel, was one of the great young prodigies of the Lithuanian Torah world at the turn of the century. At the wedding of Rav Shmuel Yitzchak Herman: Lower row: Rav Aharon Kotler, Rav Yaakov Safsel (Vishker Illui), Rav Shmuel Yitzchak Herman, Rav Avraham Kalmanowitz. Upper row behind the Vishker Illui is: Rav Avraham Trop. Rav Mordechai Elefant is to his left

In the Presence of Giants

The first months of Rav Aharon’s stay in Slabodka featured successive visits from great rabbinical leaders. He relished the opportunity to meet the aging Rav Dovid’l (Karliner) Friedman. When Rav Chaim Brisker passed through town, he commented that Rav Aharon closely resembled his father Rav Shneur Zalman Pines, who had been Rav Chaim’sstudent in Volozhin two decades prior.

When the Telzer rosh yeshivah, Rav Eliezer Gordon, arrived for a Shabbos in Kovno, the students of both Slabodka yeshivos crossed the bridge and converged upon his hotel. Years later in Baltimore, a former student at Knesses Beis Yitzchak, Mr. Harry Wolpert, described the scene: When Rav Leizer saw that hundreds of yeshivah students had arrived, he skipped the formalities and immediately launched into a shiurwith his trademark intensity. The studentslistened attentively until the flow was interrupted by a quiet but assertive voice. Who was the brave one?

Hundreds of eyes shifted their gaze towards Arke Sislovitzer. Almost as quickly as he’d been interrupted, Rav Leizer shot back, “Du ploiderst vi a shaigetz! — You babble like a shaigetz!”

That made it official. There was no longer any doubt that one of the youngest students in Slabodka was also one of its greatest, for there was nothing more complimentary in yeshivah circles than being the recipient of a full-frontal attack by the great Rav Leizer Telzer — who would regularly use barbs to buy time as his lightning-quick mind reworked his thought process.

(This proverbial rite of passage was adapted by many roshei yeshivah, Rav Aharon among them. When he delivered his shiur in Kletzk or Lakewood, it was often a challenge to follow his line of reasoning. If a student interrupted, he would yell at him, “Du redst vie a shikere Turk! — You’re speaking like an inebriated Turk!” i.e., you’re incomprehensible. And with that he’d proceed with the shiur.

Rav Shmaryahu Schulman once related a humorous incident. Rav Aharon would occasionally remark, “You know the shiur like you know Peking, China!”When some of the Kletzker students fled to China during the war, they’d quip, “Now at least we know China!”)

During Rav Aharon’s years at Knesses Yisrael, it was commonplace for elite students to go listen to Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz’s shiurim at the rival yeshivah of Knesses Beis Yitzchak. Once the students of Knesses Beis Yitzchak locked the doors, preventing these students from entering. Rav Aharon wouldn’t be deterred and climbed in through the window to hear the shiur.

While Rav Aharon regularly attended shiurim of Rav Boruch Ber, he also considered himself a talmid of Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein, whose shiurim he attended as well. Apparently, he was studying two different masechtos in depth, simultaneously.

Saved by Rav Reuven

Even while seeing success at Slabodka, there were constant pressures from family members as well as the Jewish street to conform to the pressures of modernity.

Rav Aharon Kotler’s sister Malka was relentless in trying to convince him to leave Slabodka, enroll in university, and join the modern world. Sensing the detrimental effect a steady correspondence with his sister might have on his potential growth, the Alter initiated a dramatic step. He commissioned Rav Reuven Grozovsky with the unenviable task of censoring Rav Aharon’s mail.

Eventually, Rav Aharon discovered that his mail was being censored and became extremely upset, and decided to leave the yeshivah. As he headed to the Kovno railway station, the Alter was notified and rushed to the station (another version has him sending a student). There he persuaded Rav Aharon to return to Slabodka, and thus the future Torah leader was preserved.

At a memorial gathering held for Rav Reuven Grozovsky many years later, Rav Aharon Kotler rose to speak. He choked up, and remained crying at the podium for ten minutes without saying a word. Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky then rose and declared, “I will explain why the Kletzker Rosh Yeshivah feels the way he does.” He then proceeded to share their Slabodka experiences, how Rav Reuven played a crucial role in their transfer from Minsk to Slabodka, and how he looked after their welfare there. Rav Aharon himself once stated, “Rav Reuven pulled me out of many blottes (mires).”

(Rav Elazar M. Shach witnessed the efforts of the Alter to protect his endangered students, and described the effect that this defensive mode of chinuch had upon him. Rav Asher Bergman writes that when a young illui (later to become a renowned rosh yeshivah) arrived in Kletzk, Rav Shach encouraged him to stop smoking, not out of health concerns — which they weren’t aware of at the time — but rather to ensure that should he stray from the path, at least he wouldn’t smoke on Shabbos.)

During his years in Slabodka, Rav Aharon continued to grow in learning, while also integrating the mussar lessons of the Alter. After a certain point, the Alter no longer worried about Rav Aharon being influenced negatively and set out on another mission: to prepare Rav Aharon to be a Torah leader.

During one bein hazmanim intersession, Rav Aharon had the opportunity to speak in learning with Rav Meir Simchah of Dvinsk (the Ohr Sameach), who was taken with Rav Aharon and implored his teachers, “Take care of young Aharon, he has potential to emerge as a Rabbi Akiva Eiger of the generation.”

Fused to His Shtender

In 1938 the journalist Hirsch Movshowitz (under the pseudonym M. Gertz) shared memories of his time in Slabodka in the Riga-based Yiddish newspaper Haynt in an article entitled: “The Once-in-a Generation Gaon, HaRav Aharon Kotler,” excerpted below:

Thirty-two years ago, when I came to Yeshivas Slabodka, Knesses Yisrael had a number of bochurim that were renowned giants in Torah…

Among the younger group, there were three younger bochurim [known to be exceptional], they were almost yingerlach (children): The Vishker Illui, Hershke Semiatytcher, and last but not least Arke Sislovitcher.

The youngest of them all was Arke Sislovitcher, a child of 13 or 14. He was the synthesis of both previous illuyim. He was the charif and the baki, he had the sharp mind and the breadth — but primarily the sharpness.

He was quiet, calm, easygoing, a boy tender as silk, who spent day and night learning and serving the Creator. He and his shtender and the Gemara were so attached to one another, that aside from the fact that by his bar mitzvah he was already an exceptional illui, he was less noticeable than the other two, because he and the Gemara were fused together as one, from one skin.

Everyone knew that Arke Sislovitcher was artfully entitled by the lomdishe world with the words “tzaneh malei safra — a basket full of seforim.” And an “oker harim vetachnan zeh bazeh — one who uproots mountains and grinds them one against the other.”

Despite his young age, there was great respect for him because of his brilliance and hasmadah, and that’s why no one dared to go over to the illui to “speak to him in learning.” Because, first of all, it was too audacious to try to keep up with him in Torah. Second, because no one had the heart to tear the illui away from his Gemara, which he lapped up with hasmadah like a thirsty person from a spring of water.

It wasn’t in the nature of the Sislovitzer to allow his true brilliance to be heard. I remember just one time; we were together in Romshishuk for vacation. The principal of the Kovno Gymnasium found out that among the bochurim there was an illui — a wunderkind. The Russian principal was curious to test the genius of this boy in mathematics.

[He presented] complicated mathematical problems that would be hard for a licensed engineer to solve, and the Sislovitzer resolved them in no time. Pacing up and down in the little room, he quickly supplied the answers.

The Russian principal was astonished. Was it possible? How could it be that such a small boy, who in his life never even visited an elementary school, should, on his own, immediately solve complex problems? So he came back the next day, well prepared.

This time, he planned to ask the little genius such a hard mathematical “klutz kasha” that he would gape in confusion. But what is difficult for a Russian principal, was utterly simple and straightforward for an illui from Knesses Yisrael. The Sislovitzer paced up and down the room, l’havdil like a Slabodka bochur with a difficult question in the Gemara, spun his thumb and readily solved the difficult mathematical problem. From that point on, every day the principal would send the young genius fresh eggs, fruit and other vegetables.

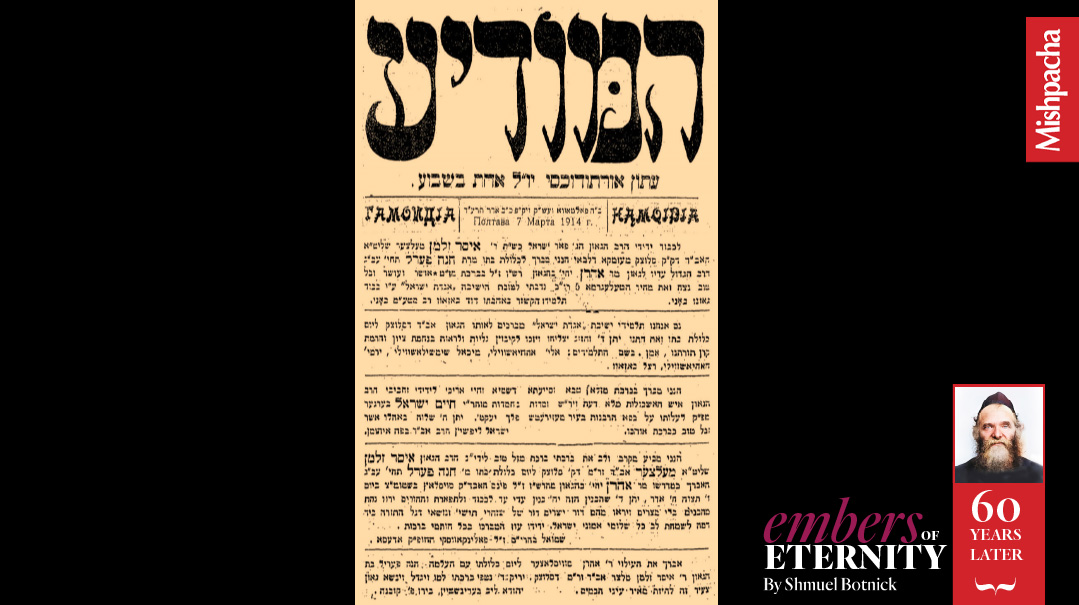

Ads in the Poltava based Hamodia wished mazel tov to Rav Aharon and Chana Perel Meltzer upon their marriage

Chapter Two: Mantle of Leadership

Fourteen Trailblazers

In 1914, following a nearly two-year engagement, 22-year-old Rav Aharon married Chana Perel Meltzer, daughter of Rav Isser Zalman and Rebbetzin Baila Hinda Meltzer. The wedding was celebrated on 8 Adar, 1914 in Slutzk. Rav Elazar M. Shach related that only one of Rav Aharon’s friends from Slabodka attended the wedding, which was the norm in those days. The kallah’s brother, Rav Tzvi Yehuda Meltzer, recalled that Rav Aharon delivered a brilliant Torah discourse, followed by a breathtaking display by his close friend Rav Avraham Elya Kaplan, who repeated the pilpul flawlessly with brilliant rhymes and a melodious tune.

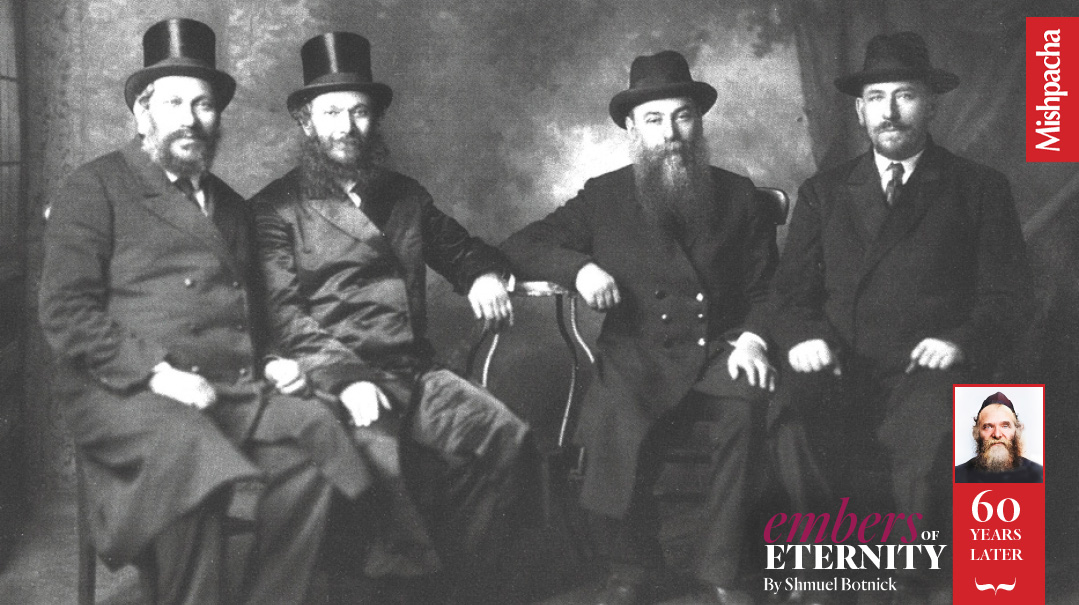

Frank’s Family Reunion: Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein (second from left) on a visit to America. To his left are his brothers-in-law, Rav Sheftel Kramer and Rabbi Pesach Frank. To his right is Rav Sheftel’s mechutan, Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak Schuchatowitz

The Story Behind the Shidduch

In 1914 the 22-year-old Rav Aharon married Chana Perel Meltzer, daughter of Rav Isser Zalman and Rebbetzin Baila Hinda Meltzer. The story of Rav Aharon’s shidduch was shared by famed journalist Rabbi Aaron Ben-Zion Shurin, who heard it from Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer while studying in Eretz Yisrael in the 1940s.

“Rav Isser Zalman told me that he’d long been aware of young Ahrele Sislovitzer, the prodigy of Slabodka, and had hopes of becoming his father-in-law one day. One day, a meshulach from Slabodka came to Slutsk and told Rav Isser Zalman about the young Aharon Kotler, describing him as ‘the lion of the chaburah.’ At that point, Rav Isser Zalman realized that the secret was out, as the collector was likely singing Rav Aharon’s praises to anyone who would listen.

“Rav Isser Zalman described to me how he rose from his chair, donned his peltz (fur coat), and informed his rebbetzin, ‘Baila Hinda, I must go finalize the shidduch immediately.’ He traveled to Slabodka and asked his brother-in-law Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein to arrange the match. The rest is history.”

Rebbetzin Baila Hinda’s father was Reb Shraga Feivel Frank, a student and devoted supporter of Rav Yisroel Salanter. He used his wealth to assist the nascent mussar movement by supporting the Slabodka Yeshivah and other mussar-linked institutions.

Reb Shraga Feivel’s youngest daughter Devorah Kramer recalled the eulogy delivered by Rav Yitzchok Elchonon Spektor, the Kovno Rav, at her father’s levayah. “Reb Shraga Feivel left instructions that no hespedim be delivered at his funeral. I would disobey his request but I am afraid of him!” With that he sat down, satisfied that he had both complied with the request and also conveyed his sense of reverence.

In marrying into the Meltzer/Frank family Rav Aharon merited a wife who had grown up in a home steeped in Torah, and solidified a connection with a family that was influential in the Torah landscape over the last century.

Prior to his passing, Reb Shraga Feivel Frank requested of his wife to ensure that their four daughters all married young men who were fully engaged in a life of Torah. Golda Frank fulfilled her promise, and took as sons-in-law, Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein, Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer, Rav Boruch Horowitz (rosh yeshivah of Slabodka) and Rav Sheftel Kramer (mashgiach of Slutzk and New Haven). Her descendants include the leadership of Chevron-Slabodka, Beth Medrash Govoha, Ner Israel, and other Torah institutions.

A story is told regarding the brothers-in-law. Following Rav Isser Zalman’s appointment as rosh yeshivah in Slabodka, the Alter wished to hire Rav Aharon Bakst as an additional rosh yeshivah. A talmid of Volozhin, Slabodka and Kelm, Rav Archik served as rabbi of many cities over the course of his long career, including Siemiatycze, Tsaritsyn (Stalingrad), Shadova, Poltava, Suvalk, Lomza, and Shavli, and a few others. In most instances he established and served at the helm of a local yeshivah as well. He and his family were martyred during the Holocaust.

There was, however, a problem. Rav Archik had once been engaged to one of the Frank daughters. The match had been broken off, because the family mistakenly perceived that Rav Archik desired to engage in the family business rather than embarking on the expected rabbinical career. Menucha Frank instead married Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein. When the Frank family heard that Rav Archik was the leading candidate for rosh yeshivah, they vehemently protested.

Rav Isser Zalman conveyed the Frank family’s position to the Alter of Slabodka, emphasizing the pain this was causing his mother-in-law, the elderly widow. The Alter then reconsidered Rav Archik’s appointment, and instead hired the Frank son-in-law Rav Moshe Mordechai as the second rosh yeshivah. With the founding of Slutzk Yeshiva in 1897, the Alter dispatched Rav Isser Zalman to be its rosh yeshivah, leaving Rav Moshe Mordechai the sole rosh yeshivah of Slabodka. That isn’t where the story ends, however.

Rabbi Shurin then added: “Rav Isser Zalman shared something personal with me. He said how, after he asked Rav Moshe Mordechai to serve as shadchan, a fleeting look crossed Rav Moshe Mordechai’s face and he realized that Rav Moshe Mordechai, who also had a daughter of marriageable age, had likely set his eye on him as well.

“‘Still,’ Rav Isser Zalman told me, ‘He didn’t say a word, or ever let on anything to that effect, and set out to make sure things went smoothly.’ Thus was the greatness of Rav Moshe Mordechai.”

Perhaps there was something else at play here. Two decades after Rav Isser Zalman spoke out on his behalf, Rav Moshe Mordechai finally had an opportunity to repay him by arranging the shidduch between Chana Perel and Rav Aharon.

(Nearly a century later, these two illustrious families came together once again when Rav Moshe Mordechai’s great-grandson, Rav Yosef Chevroni — current rosh yeshivah of Chevron-Slabodka — married Sarah Bakst, a great-granddaughter of Rav Archik.)

The new couple settled in Slutzk, where Rav Aharon soon joined the faculty of his father-in-law’s renowned Slutzk Yeshivah. The yeshivah had been founded in 1897 by the Alter of Slabodka at the behest of the rav of Slutzk, Rav Yaakov David Wilowski (the Ridbaz). Slutzk’s 10,000 Jews comprised more than 75 percent of the population. (The religious populace was predominantly non-chassidic, so much so that tradition had it included among what were said to be four exclusively misnagdic towns in the region, nicknamed “Karpas”: Kossovo, Ruzhinai, Pruzhan and Slutzk. Chassidic lore has it that Slutzk was “condemned” after the town mistreated the Baal Shem Tov.)

The rabbinate in Slutzk was one of the most prestigious in the region, having previously been held by Rav Yossel Peimer (Slutzker); the Beis Halevi, Rav Yosef Dov Halevi Soloveitchik; and later Rav Yechezkel Abramsky.

When the Alter acceded to the Ridbaz’s request and established a yeshivah in Slutzk, it was at great personal cost to his own yeshivah. In addition to sacrificing Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer, who was one of his roshei yeshivah in Slabodka, the Alter sent 14 of his finest students to Slutzk.

This group, known as the Yad Hachazakah, included future Torah leaders such as his son Rav Eliezer Yehuda Finkel, his son-in-law Rav Yehuda Leib Plachinsky, Rav Reuven Katz, Rav Alter Shmuelevitz, Rav Pesach Pruskin, Rav Moshe Yom Tov Wachtfogel, and Rav Yosef Konvitz.

Under Rav Isser Zalman’s leadership, the yeshivah emerged as one of the leading Lithuanian-style yeshivos in the Russian Empire. It was named Etz Chaim, presumably as an ode to Rav Isser Zalman’s alma mater in Volozhin.

Another member of the Yad Hachazakah, Rabbi David Rackman, who would later become a rav and businessman in Albany, described the joy exuded by the Ridbaz when he entered the beis medrash: “He would stand in the doorway virtually unseen and simply listen. Tears would well up in his eyes. He had re-sanctified a city by a simple relocation of 15 men!”

When the Ridbaz left Slutzk in 1903, the townspeople pressured Rav Isser Zalman to succeed him, and serve in the double capacity of communal rabbi and rosh yeshivah.

Prior to World War I the student body of the yeshivah had grown to more than 200, and Rav Isser Zalman embarked on a building campaign among Russia’s Jewish financial elite, culminating in the dedication of a building in 1912. In the interim he also hired a mashgiach, first Rav Shmuel Fundiler, then Rav Pesach Pruskin, and when the latter departed to establish his own yeshivah in Shklov, Rav Isser Zalman hired his brother-in-law Rav Sheftel Kramer for the position.

Luminaries who studied in Slutzk during its first two decades include Rav Elazar M. Shach, Rav Yosef Eliyahu Henkin, Rav Aryeh Levine, Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky, Rav Moshe Aharon Poleyoff, and Rav Moshe Feinstein. In addition to their regular shiurim, Rav Isser Zalman and Rav Aharon delivered halachah shiurim in hilchos Gittin and Choshen Mishpat to enhance the talmidim’s understanding of the relevant sugyos they were studying.

As the yeshivah grew, Rav Aharon’s own family grew as well. After losing a child in infancy, Rebbetzin Chana Perel gave birth to their son Chaim Shneur in 1918, followed by a daughter Sarah in 1921.

(Rav Shneur’s full name was actually Yosef Chaim Shneur. The name Yosef was added at age six when he contracted pneumonia, while Chaim was given together with Shneur because their firstborn, also named Shneur, had died in infancy. A Lithuanian tradition from the Vilna Gaon advised adding a prefix when using the name in the future. Another son, named Boruch Peretz after Rav Isser Zalman’s father, also died in infancy.)

At the behest of the Ridbaz, Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer led a group of 14 students from Slabodka to open a yeshivah in Slutzk

From Slutzk to Kletzk

Slutzk was one of the few yeshivos that didn’t endure exile during World War I, and continued to function in its original location under trying conditions of war and the subsequent Bolshevik Revolution and Civil War. When the final border was drawn between the Second Polish Republic and Soviet Russia in 1921, Slutzk found itself on the Soviet side, where the Yevsektsiya — Jewish section of the Communist Party — worked mightily to eradicate religious life.

The Yevsektsiya rightly recognized that Yiddishkeit could never coexist with Communism, and therefore aimed to destroy all institutions representing nationalism, culture and especially religion, from the traditional cheder and its melamed to the yeshivah and its dean. Their operatives held show trials and published newspapers “exposing” yeshivah students and teachers as counterrevolutionaries who were systematically poisoning the masses.

The faculty at Slutzk realized that the yeshivah would have to move away from Bolshevik sovereignty in order to continue operating, yet Rav Isser Zalman categorically refused to abandon his rabbinical responsibilities to his community. It was therefore decided to split the yeshivah. The older students would steal across the still-porous border led by the young and talented son-in-law of the rosh yeshivah, Rav Aharon Kotler. The younger students would remain with Rav Isser Zalman in Slutzk for the time being.

Rav Aharon successfully crossed the border into Poland and attempted to reestablish the yeshivah less than 40 miles away in Kletzk. The departure was painful, both for those who were leaving and those who remained in Slutzk. Reminiscing in Pinkas Slutzk, Rabbi Moshe Yissachar Goldberg, later a rav in New Orleans, described the painful scene:

“That winter day when the yeshivah was exiled from Slutzk to Kletzk is well preserved in my memory. It was after the treaty was signed between the Bolsheviks and the Poles, placing Slutzk under Soviet control. Rabbi Aharon Kotler shlita, his family, and some of the older students loaded their belongings onto a wagon and they themselves walked on foot, their heads bent and their hearts heavy.”

Crossing the border wasn’t just an escape from the anti-religious communists to the safety of Poland. It was also a symbolic — and no less daring — personal crossing for Rav Aharon.

Away from his illustrious father-in-law, Rav Aharon was now on his own. At 29 he was the youngest of Poland’s interwar roshei yeshivah, and he had now entered the public sphere as a rosh yeshivah, educator, leader and builder. The Torah world watched as its emerging leader proceeded to build one of the greatest yeshivos of the era.

Rav Aharon chose Kletzk partly as a result of its proximity to the new border, but there was a historical impetus as well. The town’s rav, Rav Chaim Shimon Herensohn, recalled that his father and predecessor had invited Slabodka to establish the branch there upon its founding in 1897. There was also a family connection as Rav Isser Zalman’s ancestors had previously been rabbanim of the town. The townspeople now welcomed Rav Aharon’s group of yeshivah students with open arms.

Rav Aharon immediately proved his leadership abilities. He promised the locals that he would pay for his students’ lodgings in what was then known as a stantzia arrangement. Their immediate needs were assumed by Rav Aharon, who had obtained a large quantity of saccharin as well as locally baked black bread. For two months the bochurim subsisted on sweetened water and black bread, with their diet supplemented on Shabbos when the townspeople hosted them for meals.

Rav Aharon at a town meeting in Kletzk (second row, third from left). The rav of Kletzk, Rav Chaim Shimon Herensohn, is on Rav Aharon’s immediate right.

Marketplace of Torah

Rav Mendel Krawiec, later rosh yeshivah of RJJ, recalled arriving for his entrance exam in Rav Aharon’s home in Kletzk: “The three-room apartment was sparsely furnished and was packed with yeshivah students who had come for their daily meal. Rav Aharon himself provided for many of the students in the early chaotic days. It didn’t have the appearance of a private residence. It was a bustling marketplace of Torah. Torah discussions filled the air, ideas debated, sugyos clarified. Amidst it all was the young rosh yeshivah guiding his students’ spiritual growth, while providing for their physical needs.”

Back in Slutzk, the remnants of the yeshivah were forced underground, and many talmidim, seeing no future under Soviet rule, crossed the border to Kletzk. The latter yeshivah’s numbers swelled as a result and by 1924 it contained 156 talmidim. Following a brief imprisonment by the Soviets, Rav Isser Zalman himself joined the yeshivah in Kletzk and resumed his former post as rosh yeshivah. But shortly thereafter, he immigrated to Eretz Yisrael where he assumed a position in the Etz Chaim Yeshiva in Yerushalayim. Once again, the growing yeshivah of Kletzk was left in the able hands of Rav Aharon.

One of the rebbeim alongside Rav Aharon was his close friend Rav Elazar Shach, who had married a niece of Rav Isser Zalman. Rav Shach remained in Kletzk through the early 1930s. (When Rav Shach assumed a position at one of the Novardok branches and later at the Karlin yeshivah in Luninitz, his family remained in Kletzk. Rav Shach would return home for the Yamim Tovim.) For the decade between 1925-35, Rav Yechezkel Levenstein served as mashgiach, and he was succeeded by Rav Yosef Leib Nenedik, who like his predecessor was a mussar product of the great Kelm Talmud Torah. He remained at his post as mashgiach of Kletzk through the onset of the Second World War, until he and his family were martyred along with most of the yeshivah students. Rabbi Yaakov Tcherbochovsky, husband of Rav Aharon’s sister Devorah, served on the yeshivah’s hanhalah as well. They too were martyred in 1941.

Rav Aharon’s focus on his studies was such that he regularly forgot to eat his meals. Rav Shaul Kagan, founder of the Pittsburgh Kollel, wrote that an older Kletzk student described how Rav Aharon once insisted on delivering the daily shiur despite a high fever. For more than two hours he stood and spoke with his usual fire and passion, occasionally pausing as he coughed up blood. “The aron was carrying its bearer,” the student aptly observed.

Rav Aharon was once in the midst of delivering a shiur in Kletzk during the snowy winter when the chimney became clogged. Soon the exhaust from the wood stove began to fill the beis medrash. Most of the students left until just a small group remained. When they felt themselves beginning to suffocate, one of them told Rav Aharon they couldn’t remain any longer. He answered, “That’s because you don’t understand the shiur. If you lived it, you wouldn’t feel the smoke!”

Public speaking, however, didn’t come naturally to Rav Aharon. Rav Shach once remarked, “You see the Rav Aharon of today, the dynamic leader. But I’ve known him since his youth. You might find it hard to believe he used to have terrible stage fright. Rav Aharon was once delivering a shiur in Kletzk when a stranger entered. Rav Aharon was overcome with stage fright because of the presence of one one unfamiliar person, so acute was his shyness. Clearly, one who accepts the responsibility of the nation’s leadership overcomes challenges beyond his nature.”

Rav Aharon (seated, far right) at a siyum in Kletzk

Groundbreaking Initiative

Rav Aharon was a forward-thinking leader who sought to establish the Kletzk Yeshivah on sound financial footing. So he hired a shadar — an official fundraiser, who in the case of Kletzk kept a full 50 percent of all earnings (a typical arrangement at the time). In 1924 this emissary was dispatched to Germany. A year later Rav Aharon complained that the system had failed to balance the yeshivah’s budget and noted in a letter that his monthly bread budget amounted to $300.

Even as the yeshivah’s deficit grew, the mashgiach, Rav Chatzkel Levenstein believed that the yeshivah needed its own building, and a building campaign was initiated. Rav Chatzkel’s daughter, Rebbetzin Zlata Ginsburg, recalled the exuberance of the Kletzk townspeople when they learned of this exciting development.

One by one, both men and women came forward with donations: money, bracelets, rings, silver pieces, gold pieces — just as during the building of the Mishkan, they offered whatever they had, and they didn’t stop there. Locals also volunteered to assist in its construction. Reb Shmuel Teitzmaller, whose family owned the local construction firm that built the yeshivah, described this exuberance decades later in a Beth Medrash Govoha newsletter:

“You could see a simple laborer or one of the balabatim grab a free moment, run over to the construction site, grab a few bricks and hand it to a bricklayer. All these Yidden wanted to save the yeshivah money, or to expedite the construction so that the building would be completed even faster — but most of all, everyone wanted some portion in this effort. They were all excited and willing to sacrifice… We would work from morning till night in the long summer days and not feel at all tired.”

Initially, the proud but small Kletzk community planned on supplementing the building fund through donations from the Kletzk Landsmanshaft communities in the United States. When this failed to produce the needed funds, Rav Aharon was forced to procure loans in order to complete the costs of the building. This further deepened the yeshivah’s deficit.

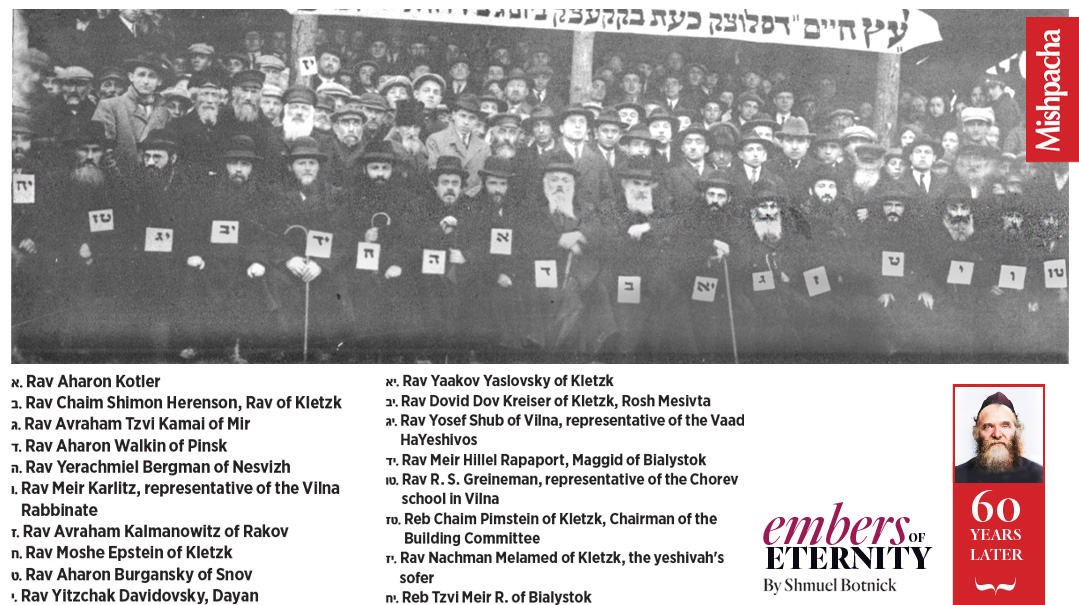

In order to generate publicity that would enhance fundraising prospects, Rav Aharon conceived the idea of a grand opening ceremony. With many rabbinic dignitaries in attendance, the festive Chanukas Habayis took place in the uncompleted building in November 1929. The special guest of honor was Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer, the former rosh yeshivah, who came all the way from Eretz Yisrael to savor his son-in-law’s accomplishments in his stewardship of the yeshivah. Upon seeing Rav Aharon after five years, Rav Isser Zalman said, “Er hut azoi fil geshtiggen (he grew so much), ich hub em nisht derkent (I didn’t recognize him)!”

The mutual respect between the two was immeasurable. Rav Aharon and his father-in-law once debated whether it was permissible for a short student to lend himself a taller appearance by inserting wooden slats in his shoes before meeting a potential shidduch prospect. Rav Isser Zalman believed the ploy was permitted, because he could retain that height by wearing the slats for the rest of his life. Rav Aharon theorized that the girl might think, “He’s a bit short, but if he were to insert slats in his shoes he’d appear taller,” therefore it would be considered deceitful. Rav Isser Zalman, who was a vaunted student of Rav Chaim Brisker and author of the Even Ha’ezel, marveled at the logic of his son-in-law.

(An interesting anecdote was related by Rav Aryeh Leib Grossnass. During his trip to Europe, Rav Isser Zalman visited the Chofetz Chaim in Radin. Rav Naftali Trop had recently passed away, and the students in Radin invited Rav Isser Zalman to deliver a shiur, after which they pleaded with him to remain as rosh yeshivah. They even locked the doors and incapacitated his waiting automobile to try and prevent his departure. Rav Isser Zalman then closeted himself in a room with the Chofetz Chaim to discuss the matter. Rav Grossnass relates, “Rav Isser Zalman left the room a half hour or forty-five minutes later, and I myself heard him saying, ‘I wouldn’t stay in Radin if I was paid all the money in the world, absolutely not!’ It turned out that the Chofetz Chaim had told him, ‘I envy you. You live in the Holy Land and serve as a rosh yeshivah. You will live for many years in Eretz Yisrael; HaKadosh Baruch Hu will yet help you, and in Eretz Yisrael you will come up with great chiddushei Torah.’

“‘After hearing such things from the Chofetz Chaim,’ Rav Isser Zalman declared, ‘I wouldn’t stay here for all the money in the world! I fully believe that whatever comes out of the Chofetz Chaim’s mouth is prophecy. It’s simply not worth it for me to stay here and miss out on such blessings.’”)

The Chanukas Habayis in Kletzk was an impressive event that enhanced the yeshivah’s prestige. After hovering at around 150 talmidim for several years, the yeshivah experienced a growth spurt in the early 1930s and by 1932 counted 230 talmidim. Rav Aharon proudly wrote to Rav Yosef Shub of the Vaad HaYeshivos that “aside from Mir and Radin, there is no yeshivah (in that region of Poland where most yeshivos were located) larger than ours.”

As the yeshivah grew in size, Rav Aharon worked to ensure it grew in quality as well. Rav Noach Bornstein, later one of the great students of the Brisker Rav, studied in Kletsk before transferring to Mir. Rav Beinush Finkel shared that on the day that Rav Noach left for Mir, Rav Aharon was absent from the yeshivah. When he returned and found him gone, he hastened to Mir with the intention of bringing back his treasured student.

The Mir rosh yeshivah, Rav Eliezer Yehuda Finkel, understood that if Rav Aharon was exerting such energy to retrieve Rav Noach, then he must be worth keeping, and so argued that he already belonged to Mir. Rav Noach himself was questioned as to his preference — to which he responded softly that had he wanted to stay in Kletzk, he never would have come to Mir.

Rav Aharon’s shiurim gained renown during the Kletzk era, and he came to be known as a great charif, a sharp and incisive thinker. Erupting in torrents of thought like a volcano, he’d cite a tradition from Rav Yisrael Salanter that “Torah is studied with venom, not with calm equanimity or coldness and apathy.” He spoke quickly. He was excitable. The in-depth analysis delivered in a staccato tone presented an intellectual challenge requiring full concentration. Rav Aharon Leib Steinman, who studied in Kletzk for a short time, described how Rav Aharon would move from one concept to another with lightning speed, requiring 100 percent focus in order to keep pace.

Following the shiur, a review was conducted by a gifted student named Pesach Horowitz and later by Shmuel Maslow, the latter of whom it was said would repeat the entire shiur without adding a single explanatory word or comment. One talmid recalled how Shmuel would recall precisely at which point Rav Aharon had cleared his throat during the shiur.

Strength in Unity

By 1924 the desperate financial straits of the yeshivos in the region led to the founding of one of the most unique organizations in the annals of the yeshivah world: the Vaad HaYeshivos.

The Vaad HaYeshivos, which was the brainchild of the Chofetz Chaim, would serve as an umbrella organization for the fundraising and budgeting operations of all member yeshivos. Under the direction of Rav Chaim Ozer and several of the leading roshei yeshivah of the 1920s, the Vaad HaYeshivos oversaw a fundraising and distribution apparatus that attempted to somewhat alleviate the burden sustained by each individual institution.

Though its focus was always financial, the Vaad ventured into other areas of yeshivah and even communal activity, including printing seforim, placement of applicants, and publishing its own newspaper.

Rav Aharon took an active and eventually leading role. He served, along with Rav Shimon Shkop and Rav Eliezer Yehuda Finkel, as one of the triumvirate of the Vaad Hapoel (executive board), which is quite astounding considering his relative age. In this capacity he maintained a very active correspondence with the two tireless administrators of the Vaad HaYeshivos in Vilna — Rav Yosef Shub and Rav Aharon Berek.

The Vaad HaYeshivos attempted to centralize fundraising efforts on behalf of the yeshivos within the Kresy region. To that end, pushkes were distributed to shuls and private homes, a publicity campaign was launched to encourage the public to donate in the local pushkes, and gabbaim were hired to oversee operations in each locality and empty the pushkes at regular intervals.

In a 1928 letter to the askanim in the field engaged in the pushke operation, Rav Aharon and his fellow roshei yeshivah of the Vaad Hapoel laid down precise instructions:

“Our experience shows us that if the pushkes are emptied more frequently, then donations are more frequent and at regular intervals. The donations are larger and the cause remains on their minds as a result as well.”

With the onset of the worldwide financial crisis and the Great Depression in 1929, the yeshivos found themselves in ever more dire financial straits. In sheer desperation, some yeshivos decentralized by engaging in local fundraising in Poland, which was against the regulations of the Vaad HaYeshivos. As a rosh yeshivah himself, Rav Aharon understood the predicament and advised the Vaad to look the other way, in a letter to Vaad secretary Rav Yosef Shub in 1933:

“You understand that at this point individual fundraising is now viewed as permissible. It is well-known for quite a while that yeshivos are engaging in decentralized fundraising based on their individual needs. We discussed this issue at a recent meeting, and it was decided that due to the current distressing financial situation there is nothing that should be done to prevent them from doing so.”

The poverty they faced was on display in another letter to Rav Yosef Shub where Rav Aharon urged, “to give on our account to the bochur, Chaim Yehonasan, 50 volumes of Gemara Kiddushin, which are needed urgently. The rest, approximately 80, will be given to us by the Vaad HaYeshivos, as they promised that they would be ready right after the holiday.” At the bottom of the letter Rav Aharon adds a note saying, “Perhaps the bookstore will accept a note from the Vaad promising payment shortly.”

Rav Aharon’s approach to communal leadership was the same as his approach to Torah study: the establishment of firm principles, broadness of scope and a most detailed conclusion.

Rav Aharon in conversation with Rav Elchonon Wasserman and Rav Moshe Blau at the 3rd Knessiah Gedolah in Marienbad in 1937

Driving Force

Paradoxically, the passing of the Chofetz Chaim in Elul 1933 provided a new impetus for fundraising. The Vaad HaYeshivos decided to honor its founder with the writing of a sefer Torah in his memory, with the proceeds going toward the support of its affiliate institutions. One of the primary movers behind this initiative was Rav Aharon. He encouraged quick action, as he was concerned that the universal impression left by the Chofetz Chaim’s passing would quickly dissipate. In a letter to Rav Chaim Ozer in December 1933, he explained:

“Time is very limited. We must immediately send out letters requesting all rabbanim and local activists to assist with organizing the campaign. Every passing day is an irrevocable loss to the success of the campaign.”

Rav Aharon even encouraged talented yeshivah students to participate as well, and many of them were sent along with rabbanim on the road for the Chofetz Chaim Torah campaign. Rav Aharon himself was personally involved in commissioning the sefer Torah; he hired a resident of Kletzk, a reliable sofer named Yechezkel Peikuss, to write the Sefer Torah, which was completed in time for the Chofetz Chaim’s second yahrtzeit in 1935.

In hindsight, this relatively overlooked aspect of Rav Aharon’s early leadership served as a prologue to his later efforts to build Torah across the ocean. In interwar Poland, one would be hard pressed to find a rosh yeshivah younger than Rav Aharon Kotler; most of his fellow roshei yeshivah were twice his age. Yet his sense of responsibility for the wider yeshivah world was astonishingly broad. He may have been young, but he was quickly emerging as a driving force of true leadership.

In addition to the respect that Rav Aharon garnered as a rosh yeshivah and Torah leader, he was also occasionally asked to opine on halachic issues. When the Nazis enacted a law in Germany during the 1930s banning traditional shechitah, Rav Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg of Berlin wrote to halachic decisors of the time to elicit their opinions on whether German Jewry could rely on a leniency to stun the animals prior to shechitah. Rav Aharon ruled against this leniency, even for those medically required to eat meat, concerned for the precedent such a dispensation would create.

Rav Yaakov Teitelbaum, leader of the Zeirei Agudah in prewar Vienna and later the rav of Adas Yereim in Kew Gardens, told of a rabbinic gathering in Europe attended by Rav Chaim Ozer. An issue was debated and Rav Aharon, not yet 40, stated his opinion. An elderly rav exclaimed, “Yungerman, sit down. Who are you to speak in the presence of gedolei hador?” Rav Chaim Ozer retorted, “Der yungerman darf men tzu heren vail der nexter dor vet zein oif zein pleitzis — we must pay attention to what this young man has to say, because the next generation will rest on his shoulders!”

This point is further reinforced by a story shared by Rav Aharon Lopiansky. One of the Torah giants of prewar Europe, Rav Mottel Pogromansky, once asked someone to call Rav Aharon on his behalf. When Rav Aharon got on the line, the caller respectfully referred to him as “Kletzker rosh yeshivah.” Rav Mottel exclaimed, “Kletzker rosh yeshivah? The rosh yeshivah! Rav Aharon is much more than just the rosh yeshivah of Kletzk!”

Rav Aharon delivering a shiur in Kletzk

“In listening to Rav Aharon, one always sensed the genius of a deep and penetrating mind arriving at simple conclusions. His approach to learning was creative and vital. In Poland, when there were many yeshivos, people would say, if you would like an approach full of life (lebedeigkeit) then go to Kletzk. True, his shiur consisted of cool logical analysis, but when he spoke, it was a fiery volcano. He gave lie to the myth of the ‘cold Litvak,’ the fire of his great soul manifesting itself in his personality as in his words and deeds”

— Hillel Seidman

Principles Before Politics

Almost from its inception, Rav Aharon was supportive of and active within the Agudas Yisrael political party in Poland. His father-in-law, Rav Isser Zalman, attended the first Knessiah Gedolah in Vienna in 1923, and Rav Aharon himself attended and served in an active role during the crucial third Knessiah Gedolah in Marienbad in 1937.

A report on that Knessiah in Hapardes states that, “Rav [Elchonon] Wasserman, Rav [Aharon] Kotler, Rav [Mordechai] Rottenberg from Antwerp and rabbis from Czechoslovakia and Hungary were in agreement in rejecting any proposal for a Jewish State on either side of the Jordan River, even if it were established as a religious state, because such a regime would be a form of heresy in our faith in the belief in the coming of the Messiah, and especially since it would be built on heresy and desecration of the Name of G-d.”

In the highly politicized atmosphere of interwar Polish Jewry, education — like every other facet of communal life — generally operated within a political affiliation with a specific party and political platform. Due to fundraising concerns, yeshivos generally refrained from overt association of this sort. Rav Aharon, however, had no qualms about taking blunt political positions, even if it meant alienating donors who were Mizrachi supporters.

Decades later a similar issue arose in America, when Rav Aharon led a landmark 1956 ban against participation in mixed-denominational boards of rabbis. In the postwar period, Rav Aharon would be universally recognized as an Agudas Yisrael leader in the United States, and more surprisingly, even in Israel. Following Rav Reuven Grozovsky’s incapacitation in 1952, Rav Aharon assumed the role of chairman of the Moetzes Gedolei Hatorah of Agudath Yisrael of America. He took strong stances on many contemporary issues in both the US and Israel, and elicited anger from supporters with his vocal protests against Israel’s draft law for women as well as the ensuing proposal of Sherut Leumi. Nothing could stand in the way of Rav Aharon’s lifelong pursuit of truth.

(On one of Rav Aharon’s visits to Israel, a Yerushalmi Jew requested a brachah for his young son from Rav Aharon. He acquiesced and blessed him to become a talmid chacham.

“Gib a brocha zohl ehr verrin a kannai — bless him that he become a zealot,” the father pressed, but Rav Aharon demurred, “If he’ll become a talmid chacham he’ll know how to conduct himself.”)

Israeli Agudah politician Rabbi Shlomo Lorincz once asked a man whose lifestyle seemed different from Rav Aharon’s ideals why he was a donor to Beth Medrash Govoha. He answered that Rav Aharon’s personal magnetism was what drew him in, but even more so, he was impressed that Rav Aharon spoke with such enthusiasm and persuasiveness while maintaining his integrity, something he rarely encountered among other rabbis who solicited him.

The Mizrachi leader and Warsaw-based lawyer Zorach Warhaftig, who enjoyed a close relationship with many leading roshei yeshivah including Rav Aharon and would later play a vital role in the rescue of yeshivah students and roshei yeshivah during the war years, recounted in his memoirs his conversation with Rav Aharon regarding one facet among others of his general opposition to Zionism:

“In my many conversations with Rav Aharon Kotler, similar to my ones with Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzinski, I got the impression that they view the study of Torah and the love of Torah as an all-encompassing outlook. They were concerned that love of Zion and Jerusalem would compete for adherents among Jewish youth, and that the latter love would take the place of the former.”

In this regard, Rav Aharon even disputed the position maintained by his own father-in-law. Rav Isser Zalman immigrated to Eretz Yisrael in 1925 and obtained a certificate on behalf of one of his talmidim in the yeshivah who wanted to go as well. When Rav Aharon heard about it, he forbade the talmid from going along, saying, “I forbid you from going! You won’t do well there, there are many apikorsim there.” When the bochur made it clear that he still planned on utilizing the certificate obtained on his behalf by Rav Isser Zalman, Rav Aharon asked him to leave the yeshivah.

As time went on, however, and the security situation in Poland necessitated emigration, Rav Aharon often penned letters requesting certificates to Palestine on behalf of talmidim who requested his assistance. He’d clarify that his fundamental position hadn’t changed; it was rather counterbalanced in individual cases when specific needs arose (such as financial straits, the military draft, etc.).

Rav Aharon and Rav Shlomo Heiman in Camp Mesivta.Following Rav Shlomo’s sudden passing in 1944, Rav Aharon volunteered to fill in and say his shiur during the week. After a couple of days Rav Shraga Feivel approached Rav Aharon and proposed that he stay in the position long term. Rav Aharon turned him down. The rest,as they say, is history.

Bitter Days in the Goldeneh Medineh

Even with assistance from the Vaad HaYeshivos and Joint Distribution Committee, meeting the yeshivah’s budget remained a constant challenge. Rav Aharon used to say, “The acronym of Rosh Mesivta is RAM, which when reversed are the letters MAR, which means bitter. It is a great honor to stand at the helm of a packed beis medrash and teach Torah, that is RAM — lofty and elevated. The other side of the coin is the financial struggle, which is MAR — bitter.”

A floundering Polish economy, devaluation of the Polish zloty and the yeshivah’s growing debt meant that Rav Aharon would need to follow the path of other roshei yeshivah and travel abroad to raise funds.

In 1933 he traveled to England and Ireland, but it became apparent that the yeshivah was on the brink of financial collapse. He sensed that he would have no choice but to embark on a journey overseas to the home of the largest and most prosperous Jewish community in the world — the United States of America.

While Rav Meir Shapiro, Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz, Rav Eliezer Yehuda Finkel, Rav Shimon Shkop and others had conducted fundraising trips to America in the 1920s with varying results, no one had attempted such a journey since the stock market crash of 1929 and ensuing Great Depression. The economy was finally on the upswing, but the depression wouldn’t end until 1939 and funds were still tight for many. Still, Poland’s economy was mired in an even worse depression, and Rav Aharon hoped that Jewish hearts and wallets would open to their needy brothers abroad.

On September 10, 1935, Rav Aharon arrived in New York on the RMS Majestic. In advance of his arrival, The Morgen Journal profiled the Kletzker rosh yeshivah:

“Rav Aharon was already known in his youthful years in Slabodka as the Sislovitzer Illui. …From year to year he grew in his brilliance, and now he is among the giants of the generation. There is no doubt that even the greatest rabbanim and lomdim of New York will be amazed when they will have the zechus to get to know the gaon, Rav Aharon Kotler, the Kletzker Rosh Yeshivah, who is great not only in his Torah learning, but also in worldly knowledge.”

The administrator of Kletzk, Rav Shimon Goder, who would later serve as administrator in Torah Vodaath, had arrived in America three months prior and now joined Rav Aharon during his fundraising appeals.

Rav Aharon spent a Shabbos in East New York as the guest of Rav Tzvi Hirsch Dachowitz, an old friend and respected rav. Rav Aharon addressed the crowd and then Rav Dachowitz announced that for $12, one could cover the expenses of a student for a month. A simple peddler named Tzvi Moshe Cohen stood up and announced that he would pledge $12. He was soon followed by several others, and the appeal was a success.

Immediately after Shabbos, Mr. Cohen rushed to Rav Dachowitz’s home to fulfill his pledge. Rav Dachowitz whispered to Rav Aharon: “You must understand what is going on here! This man is legally blind and hardly has any money to his name. He earns a mere $12 a week as a peddler, and he’s donating his entire weekly salary to the yeshivah.”

Rav Aharon was so moved by this act of mesirus nefesh that he jumped up from behind the table to where Mr. Cohen stood. Thanking him profusely, he blessed him with nachas and greatness in Torah from his children.

His son is the great posek, Rav Dovid Cohen, rav of G’vul Yaavetz in Brooklyn.

On Erev Rosh Hashanah 1937 Rav Aharon wrote to Mr. Cohen: “With a deep sense of gratitude, I recall your love of Torah and generosity, and without taking into account your own dire straits, you donated a number of times more than you were able to. May Hashem consider it a great tzedakah.”

Rav Dovid Cohen related to us a postscript to the story. On December 7, 1941, at the funeral of Rav Dovid Leibowitz, Rav Aharon spotted Mr. Cohen out of the corner of his eye and once again thanked him profusely for his selfless act. It had clearly made a deep impression on Rav Aharon.

When Rav Aharon told Reb Shraga Feivel of his plan to open the yeshivah in Lakewood, without hesitating, Reb Shraga chose some of the Mesivta’s best — including Rav Elya Svei, Rav Yisrael Kanarek, and Rav Yaakov Weisberg — and sent them to Rav Aharon. The roshei yeshivah in Torah Vodaath were understandably upset to lose such prize pupils and complained to Rav Shraga Feivel. He told them unapologetically, “Our task is to cause Torah to flourish, and Rav Aharon cannot be rebbi for students of a lower caliber.” (Photo from the 1947 Torah Umesorah convention in Cleveland)

On the Road

During the course of his 11 months in the United States, Rav Aharon visited locations from Boston to Atlanta, New York to Nebraska. He was introduced to admirers who would become his loyal supporters. Most important was a partnership initiated with Mr. Irving Bunim, who was to emerge as Rav Aharon’s closest confidante for the next three decades.

Whether it was rescue work during the war, building Beth Medrash Govoha, the establishment of Chinuch Atzmai, Torah Umesorah, and almost every endeavor which Rav Aharon would participate and initiate towards the building of postwar Orthodoxy, he’d do so with Irving Bunim at his side.

Other supporters of note were Mrs. Necha Golding and her husband Sam, who hosted Rav Aharon in their New York home. Mrs. Golding also founded the yeshivah’s sisterhood, galvanizing local women to support young men dedicated to Torah learning. At her funeral many years later, Rav Aharon delivered the sole eulogy while crying copious tears. “She was the tzaddeikes hador. There will never be another like her.”

Rav Aharon was also assisted by two young rabbis, Herbert Goldstein and Leo Jung, who made introductions to wealthy congregants and hosted a large tribute event. Another organizer of the New York event was a former Slutzk talmid named Zadok Kapner, a brilliant scholar who had become a successful physician but was still said to be one of the greatest Talmudic minds in America.

During this trip, Rav Aharon spent a significant amount of time in Baltimore. His relative and close friend from Slabodka, Rav Yaakov Yitzchak Ruderman, rosh yeshivah of Ner Yisrael, arranged a number of appointments for Rav Aharon.

At one meeting, Rav Ruderman introduced Rav Aharon as “one of the geniuses of our times, a rosh yeshivah for outstanding pupils.” The man leaned toward Rav Ruderman and requested to speak with him privately.

“Listen,” said the man without the least bit of cynicism. “I like the look of this Jew. Perhaps he’d be willing to become my community’s shochet.”

Rav Ruderman remained bothered by this for quite some time.

The travails of the months Rav Aharon spent on the road are evident in letters he wrote during this time. In a letter penned in Toledo, Ohio, he addresses a query on the subject of “masneh al mah shekasuv baTorah,” and apologizes “because of the great exertion and due to the weakness of my health, as I caught a cold and can’t elaborate.”

He continued: “In Columbus, Ohio $130 dollars was collected; Yesterday evening, we came to Toledo, the rav here Rabbi Nechemia Katz (brother-in-law of Rav Moshe Feinstein) studied at our yeshivah in Slutzk, and of course he is trying to do everything possible…” He also wrote that he considered traveling to Cleveland for the coming Shabbos, but received word that representatives of the Slabodka yeshivah had preceded him. Rav Yechiel Mordechai Gordon of the Lomza Yeshivah was traveling to Detroit, as “it was already scheduled for him earlier, therefore I don’t know yet where we will be for Pesach.”

Rav Aharon arrived in Indianapolis and proposed joining Rav Shmuel Isaac Katz, the local rav, for Shabbos, but the latter (who was clearly unaware of Rav Aharon’s stature) demurred, proposing that Rav Aharon stay at the local community hekdesh (guest hostel), where meshulachim were generally housed. When Rav Aharon insisted, Rav Katz immediately proposed a compromise.

“Although right now I really can’t host you or help you fundraise, I also can’t just absolve myself without doing anything. You know what? I’ll test you and if you pass, you are invited to join us for Shabbos. I can’t refuse a bona fide talmid chacham!”

He then asked Rav Aharon to locate five different passages in Talmud Yerushalmi and Rav Aharon knew them all, earning the right to be Rav Katz’s guest. Rav Aharon later related how much he enjoyed talking in learning with Rav Katz. “He had a mind like the Rogatchover,” Rav Shneur recalled his father saying.

Planting Seeds in American Soil

Much of the difficulties faced by Rav Aharon in America stemmed from the fact that Kletzk was a relatively new yeshivah and didn’t have many alumni serving in prominent roles in America to assist in making connections and collecting multi-year pledges Rav Aharon had received. Letters to Mrs. Necha Golding in the years following the trip beg her to follow up on pledges from others that went unpaid. Senior yeshivos like Mir and Slabodka had alumni networks that greatly assisted with this process. Those rabbis also encouraged advanced American yeshivah students to study in Mir and Slabodka, which generated publicity as well.